Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Just a dumb comedy?

Jack Atkinson

Douglas Adams was something of a hero of mine. If the legends are true, he went to school with the elite—the politicians and the bankers—and he developed a distinct and perfectly rational lack of respect for them.

He dreamed of working in the media, but it’s a tough field to get into unless you completely lack any of the basic tenets of humanity. Fortunately for him, his work as a bodyguard didn’t really suit him, so he doubled his efforts to crack into the entertainment industry, even stooping low enough to work in BBC radio for all 7 of the people listening.

Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy may, or may not, have started out due to an incident where he was hitchhiking around Europe and struggled to find a place to stay due to nobody being able to hear or understand him. He laid in a field, got drunk, and contemplated the ridiculousness of the universe, later discovering there was a conference for the deaf being led in town. This story he told may not have finally put the story straight—or at least firmly crooked—but it does give an insight into the kind of man Douglas Adams really was.

Unlike the people he was educated with, he wasn’t wealthy and he had a curiosity about life, and a connection to the world. This was a man who went out to find his path, not to follow along on someone else’s.

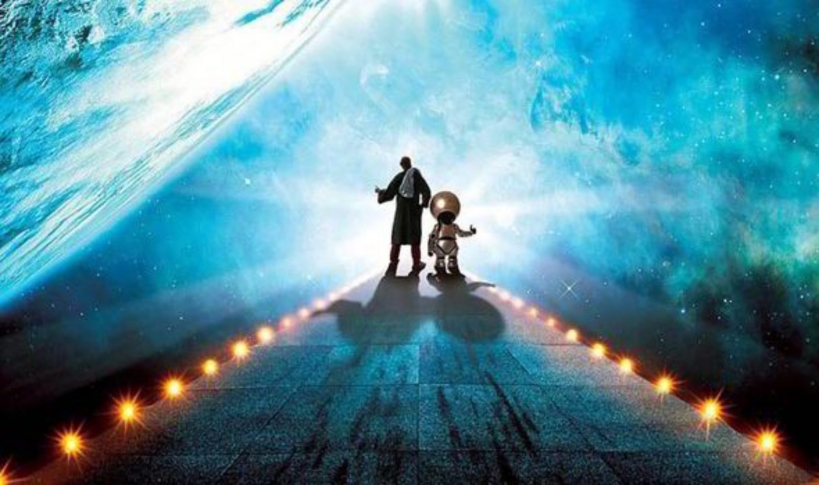

Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy began life as a short radio play about the end of the world, but the story was recognised to be interesting enough to develop itself into a series, and then a further series of books. It later spun off into a television series, a video game, an unreleased calendar and a movie that probably should have remained unreleased as well. Each iteration varied slightly in terms of plot, so that every version had a unique twist. It’s the novels that have the most detailed and interesting plot.

While the radio play set the basic elements of the story ‘firmly crooked,’ and the television series is generally considered the standard by which all other versions are measured, it’s the book that really set the story more firmly, and less crooked.

Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy was a best-seller, a rare thing for a science fiction story and it made its author a very wealthy man—something even rarer still. The popularity came in a large part from the fact that the story was a comedy in the truest and most British sense. It wallowed in its sense of the ridiculous, and was one of very few books that was actually laugh-out-loud funny.

Like the story from which it grew, it details the end of the world, as Earth is demolished to make way for a hyper-express-way; or some such nonsense. The only survivor from our world is a slightly bewildered man who is dragged kicking and screaming into a larger galaxy by his alien friend, who was under-cover writing an article about our planet.

The story is, on the surface, just a fantastic slice of ridiculous craziness that channels just a pinch of that Monty-Python brand of comedy. Or, is it just a bit more than that?

The protagonist is Arthur Dent, a man who is about to embark on an epic journey into the unknown. He works for BBC radio, and is a normal, everyday man. He is a humble reflection of the author, an ‘everyman’ character we can imagine and project ourselves into. He takes the writer’s personal experiences as a scaffold around which his character is developed.

This tells us that Arthur is especially grounded, a person we can imagine to have a solid basis in fact. While the rest of the story goes off at wild and often unimaginable tangents, Arthur is a stable anchor around which our perception is safely tethered.

The story has a supporting cast of characters that are far less mundane, the main players being Ford Prefect, Zaphod Bebblebrox and Marvin. On the surface, these characters seem like fascinatingly odd and imaginative creations but they’re subtly more than that.

Marvin represents the downtrodden workers. He is intelligent and capable, and all the actual labour is given to him, work far beneath his capacity, and tasks that demean his abilities. He represents the working-class, a group who submit to authority and who have been crushed into depression and misery by endless, thankless service.

Zaphod is a two-headed, and thus two-faced politician that has risen to prominence by his abundant charisma, instead of any suggestion that he has any degree of ability. He represents the psychopathic political leadership that Adams saw around him. He has three arms, a metaphor for a man who hugs you while his spare hand is reaching into your pocket. He cares nothing for the feelings—or even survival—of others, and is solely driven by self-interest. He is the ruling class, privileged and incapable, kept in authority by the ignorance of those around him and the system that keeps him there.

Ford Prefect is a strange joke that’s slightly out of time. He is named after a car, after mistaking the dominant species of our planet for the automobiles that we humbly serve. Douglas Adams was a firm believer in the environment and this was a pointed barb at selfish consumerism. Ford, the character, is a manifestation of the creative spirit. He lives in our world, but comes from another and does his best to fit in. Of course, he can’t. He’s seen a larger, better world, and that makes him something of an outlier. He isn’t just a character, he’s our guide into a larger, stranger world.

There are also a host of other characters who represent various ideas to lesser or greater degrees. Trillian comes from an era where women were not always treated entirely fairly, and she plays the role of a remarkably capable person who is viewed unfairly because of her gender—but that is tempered by the fact that her presence on the ‘Heart of Gold’ is due to the same sexuality she’s trying to ignore. The Vogons are a race of aliens, not evil, but governed by unnecessary bureaucracy, a thing that eventually causes the end of the whole planet, thanks to their heartless application of it. Trillian represents the illusion of equality while the Vogons are the middle-managers, the governments working for the elites. This idea comes back at the end of the second novel as a larger plot-device.

The story, and mostly the first novel, has several themes and metaphors embedded in it. An unnamed (until a subsequent book) woman at the beginning of the story has an idea about how to restructure the world so that it would be fair for everyone. It comments about how this method would mean that, this time, nobody would need to be nailed to a tree. Douglas Adams, an atheist, dropped in several comments about religion and his general opposition to it—some more obvious than others.

But there was another, larger theme that comes up often and that’s about the world’s banking system. There are frequent commentaries about the ridiculousness of the galactic financial industry, eventually culminating in the very rich having the option to build custom planets. The physical currency is so large that it’s impossible to carry, and its triangular, like the pyramid on the back of a dollar bill—the one with the all-seeing eye symbol.

Adams goes further still, naming the primary ship, the ‘Heart of Gold.’ The name doesn’t relate to the story directly but makes perfect sense when you interpret it as the ‘Gold Standard’ upon which modern financial and government models are based. Once you start looking into who Douglas Adams was and what he believed in, all of these things start making a whole lot of sense.

Eventually, the main theme of this story, at least in terms of the book, is repeated several times. It’s laid out in plain sight for anyone to see, if you just know to look for it. Adams tells us over and again during the story that, ‘the world is not what you think it is.’ The message coming loud and clear from this work is that Arthur Dent is him, and by extension, all of us. He’s found himself dragged into a much larger galaxy that he knew existed, but tried to ignore, and now he’s dealing with the reality of things. Instead of a participant where he couldn’t see the wood for the trees, he’s now able to be an observer of how things really work. He sees the working class and the politicians for what they are and sees how they manipulate things in their favour.

With the pieces in place, they go off on a quest to discover the meaning of life itself and discover that everything was a lie, on top of a falsification, built on top of a fraud, and Arthur was always a tiny part of it, helpless and ignorant.

Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy is anything but a dumb comedy. It’s a serious reflection on the life the author led, and the people he met along the way, with jokes plastered on top.

A comedy makes us laugh. It’s fun to watch someone slip over on a banana-skin, but that’s not something that inspires conversations and decades of interest. It takes metaphors, themes and characters that represent something more to get home the message, and Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy has all of those things. This story is a lot deeper and smarter than most people ever imagine, and this article barely scratches the surface of what there is to find.

You see, there are two kinds of art. The first, like most modern music might be great at first, but as we listen more, it bores as as there’s nothing of value to it. The second kind rewards us with every subsequent viewing, because it’s built on a framework that matters.

Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy is not the first kind.

Many thanks for reading this article. We hope it was interesting, informative and entertaining. Follow us on social media or share our content on your own pages. It helps us grow so we can create more free content to help you.

Want a completely free sci-fi comedy?

Rob is a ginger waiter who successfully fails at dating. Dave delivers towels. Join them on an adventure that might change the entire galaxy – but won’t – as they drink free beer and travel out to the edge of the known galaxy for reasons that barely seem worth boring to mention.